Tuesday, November 30, 2010

Thursday, November 25, 2010

Q and A with Cameron van der Burgh

Note this article was commissioned by SA Sports Illustrated.

How do you swim breaststroke? What’s the secret?

Breaststroke is the most technical of all the strokes. You need good timing, control and rhythm. If you get too excited, or try too hard, your hands and legs start to work against each other. The tall guys struggle, because in breaststroke you need a high stroke rate, and to do that you need to be able close your legs at the end of each kick quickly. It’s also about having a good feel for the water.

Are you the captain of the South African swimming team?

I’ve sort’ve been assigned to mentor some of the up and coming swimmers with a focus on 2016. My focus is 2012. So I’m more of a big brother and I try to share some of the tricks of the trade with guys like Chad le Clos and Charl van Zyl. You learn from experience that small things at our level can make a big difference in the end.

Such as?

Walking in slops. At the Commonwealth Games you walk around a lot. If you wear slops it tires your calves out, and by the fourth or fifth day you really start feeling it.

And how is Ryk involved?

Ryk is my agent. He manages my media; he gets sponsors for me. He has got a lot of contacts, he knows how to sell and he’s done well in terms of sponsors. My main sponsors are Investec and Tag.

I started swimming when I was four, and was burned out by the time I was twelve. But you got a very late start didn’t you?

I’ve been swimming since the age of 11 which is a lot later than a lot of people. It started at an Interhouse competition at school. I hadn’t really swum before and I won. In 1998 I swam for Northern Transvaal B, the following year for the A team, and in 2000 I made the South African team for the first time. I was 20 years old when I swam my first Olympics in 2008.

How did you do?

Mixture. I went into the Olympics ranked 16th. I did well in my heats; I was ranked fourth going into the semi final. I was so ecstatic I couldn’t sleep. But then we had the finals in the morning in Beijing. Television channels in the States paid a lot to switch around the times, because we usually swim the finals in the evening. I slept about two hours and then missed the final by something like 0.02 seconds. So it messed us all around. I’m better now at controlling my emotions. It comes down to that experience thing.

So what have been some of your career highlights?

I’ve broken 11 world records. In 2009 I got gold at world championships. In Delhi I beat the reigning 100 metre world champion, Brenton Rickard. I’m currently the world record holder in the 50 metre breaststroke [26.27 seconds] and in the short course [25m pool] in the 50 metre and 100 metre breaststroke [25.25 seconds and 55.61 seconds respectively].

What was India like? Did you have any problems with the crowd?

I didn’t think it was that bad. The first two days it wasn’t that crowded. A lot of tourists didn’t make the trip because of the threat. In the last three days they cut the admission prices and from then on the stadium was packed.

I’ve seen your physique. I don’t think I’ve seen a swimmer with a bigger chest than you. Is it genes, gym or graft?

I’m a sprinter so it’s all about power. If you lose your power you lose your rhythm and you start going nowhere really fast. You just die. Training hard when your body is developing, you know from a young age, definitely translates to big shoulders. Even the girls experience that. And breaststroke is such a power stroke. To do well in breast you have to be shorter, stockier and stronger. LJ van Zyl [400m hurdler] laughs at me when I run, because I have stubby legs and big torso. Physique comes with the training. I swim 11-12km per day, 30% of that is breaststroke. If we do more we start to hurt the knees. And we do a fair amount of gym work. Lots of pull-ups [he can do 75 continuously] benchpress, clean and jerk...

What’s your poison?

I really love coffee. I’m a real coffee addict. Tomorrow we’re shooting for Top Billing and they’re going to teach me how to brew the beans, what temperature to heat the milk. I enjoy Vida e’s Cappuccinos. In Pretoria we don’t have that many though.

You seem really relaxed. Aren’t you strict about diet?

I listen to my body. But if I’m craving a chocolate or a cup of coffee I’ll have one. I can afford to eat a bit of junk food because we just burn it all off. One day it will be a lot more difficult because as you get older you put on weight easier.

What about goals?

I’ve already achieved most of my goals. [Broken a world record, world champion and Commonwealth champion]. All I’ve got left is to become the Olympic champion. Thanks to funding from Sascoc and sponsors, and my coach Dirk Lange, I’m on track.

You look a lot like Graeme Smith.

[Chuckles] I get that a lot. Everyone in the world has a lookalike. I know some of the cricketers and it’s not an insult to me. I’d really like to meet him.

Sunday, September 26, 2010

Mzanzi Down Under

In February this year I jetted off to Perth, Australia, and for an entire month I bicycled, boated, flew, took the train, hired a car or hitchhiked all the way round the island continent. I arrived back in Perth 28 days later, physically and financially a shadow of my former self. Going home, platsak, I realized this devilishly hot and humid country doesn’t put Mzanzi in the shade; not by a long shot.

Australia has their iconic yellow and black kangaroo sign right? Well we have our jumping kudu framed by a red and blue triangle. Our flying kudu is way cooler. They have Bell’s Beach, we’ve got J-Bay. Earth’s largest living organism, the Great Barrier Reef, isn’t such a big deal. For starters it’s miles offshore and it’s in a remote part of the country. Once you’re there it’s like any other reef, just bigger. But let’s dig a little deeper, shall we.

Good Railways, Silly Road Signs and Police on Steroids

Australia’s public transport is top notch. All of their big cities have the equivalent of a Gautrain except for Darwin, which was flattened in 1974 by a category 4 cyclone. Although theirs are beautifully integrated and modern cities, Australia is unfortunately an extremely expensive country, so much so that Australian’s fly outside Australia when they go on holiday, to cheaper places like Bali and Phuket.

For a gigantic country like Oz, the 110km/h strictly enforced speed limit is excruciating. And another kind of nanny-state hell exists for those road users stuck for hours on the road: plenty of ridiculous road signs and a hundred extra rules to abide by. There are warnings for everything; from crests to dips in the road, from signs cautioning about soft sand on the beach to unexpected waves.

You can be fined at the airport for bringing foreign dirt into Australia [check the soles of your shoes], or, gasp, your favorite cereal. The thinking goes that a stray oat kernel might sprout in a sand dune and infiltrate the Outback.

8 Times

You might think a country 8 times the size of South Africa [and the world’s 6th largest country] would have 8 times more to offer, but unless you’re a sand salesman, you’d be wrong. Australia’s size means it’s moer far to get around. Nullaboor in Western Australia is as flat as a pancake. The track that crosses the Nullaboor is the world’s longest straight section of railway line in the world. Ja, it’s pretty boring.

Perth, 3300km from Sydney, is one of the world’s most isolated cities. Imagine having to travel from Cape Town to Pretoria just to get halfway to Johannesburg.

But the number one issue facing this mammoth country, believe it or not, is climate change.

Heat

Crime can seem like the worst problem in the world, but it’s fiddlesticks compared to Australia’s climate conundrum. It’s ironic that being the world’s number one coal exporter, Australia has the highest per capita level of emissions in the developed world, and they’re reaping a whirlwind of climate problems In February they have to endure constant, unbearable heat across the length and breadth of the country.

When I visited Melbourne’s average temperatures were the highest since records began. Many other centres set new all-time records too. It was hot, and rainfall was either absent or miserly figures like 0.2mm for the entire month. In Perth we measured the heat ourselves; at 7pm it was still 37 degrees Celsius. This heat turns Australia’s forests into a tinderbox, and when they burn the damage is catastrophic.

On a trip to the famous Pinnacles Desert two hours north of Perth the mercury shot up to 44C in Cervantes. Imagine standing with your ankles in the sea, and the rest of your body feeling like it is stuck in a gym sauna; the air so hot it pinches the soft linings of your nose. The Pinnacles is basically a graveyard of rocks in a sandpit the size of 5 rugby fields.

Humidity

I found the humidity a problem everywhere in coastal Australia, from Perth, to Sydney, with Darwin being the worst. Without an air conditioner in Australia you’re toast! At night you lie naked except for a scrap of underwear in your tent; you’re a pathetic, heaving foetus, trying to survive overnight in the sauna conditions. You’re covered in a permanent film of sweat, bugspray and sunblock. You wonder, maybe it’s your own body heat and breath causing the infernal heat in your tent – but when you open the tent flap at 4am it’s just as warm outside. And how do Australians suggest we cope with the infernal heat of the day? “Take hot showers,” they say.

Further up the coast of Western Australia is the attractive town of Broome, one of the fastest growing centres in Oz. It has camel rides on the beach, a section that boasts the largest collection of dinosaur footprints in the world [except it’s underwater] and special gutterless roofs because when it rains it pours so much the water literally rips the gutters off the eaves.

Jellyfish

Broome seems like a lekker place. Cable Beach has that classic sickle shape. But you realize something is wrong when it’s the height of summer, it’s mid to high thirties and uncomfortably humid, and despite the national holidays, not a soul is swimming in the sea.

It turns out that this is one of a bunch of nasty consequences of climate change haunting virtually the entire coastline: floating clouds of poisonous jellyfish and stingers. I scoffed at the warnings at first, until I was stung by something so small I couldn’t see it. It left a yellow bruise on my chest for weeks.

This was one of the most frustrating aspects of visiting Australia. The height of summer, and miles and miles of gorgeous coastline but it’s too dangerous to swim in the sea. When I visited the Great Barrier Reef we all had to pay for stinger suits, which effectively cover 90% of your body. But you can still get stung on exposed parts like hands, feet and cheeks. What’s the fun in swimming in summer dressed like a glove?

Wallabies VS Springboks

When the nickname for Australia’s national animal is also the longer version of a term we use to say someone ain’t too bright, you’ve got to hand the trophy to the Boks. In contrast to a Wally, a Bok is up for anything. Calling someone a Bok is a compliment. Kangaroos, in Africa, against our predators, wouldn’t last more than a few blinks after sunset. And that should put paid to the question surrounding whether the Wallabies are better than the SpringboksBut here’s the clincher. The fact that you can buy boerewors and biltong in Australia, and it's called boerewors and biltong, says a lot about what a lot we got. In every area we give Oz a real run for its money.

Australia has their iconic yellow and black kangaroo sign right? Well we have our jumping kudu framed by a red and blue triangle. Our flying kudu is way cooler. They have Bell’s Beach, we’ve got J-Bay. Earth’s largest living organism, the Great Barrier Reef, isn’t such a big deal. For starters it’s miles offshore and it’s in a remote part of the country. Once you’re there it’s like any other reef, just bigger. But let’s dig a little deeper, shall we.

Good Railways, Silly Road Signs and Police on Steroids

Australia’s public transport is top notch. All of their big cities have the equivalent of a Gautrain except for Darwin, which was flattened in 1974 by a category 4 cyclone. Although theirs are beautifully integrated and modern cities, Australia is unfortunately an extremely expensive country, so much so that Australian’s fly outside Australia when they go on holiday, to cheaper places like Bali and Phuket.

For a gigantic country like Oz, the 110km/h strictly enforced speed limit is excruciating. And another kind of nanny-state hell exists for those road users stuck for hours on the road: plenty of ridiculous road signs and a hundred extra rules to abide by. There are warnings for everything; from crests to dips in the road, from signs cautioning about soft sand on the beach to unexpected waves.

You can be fined at the airport for bringing foreign dirt into Australia [check the soles of your shoes], or, gasp, your favorite cereal. The thinking goes that a stray oat kernel might sprout in a sand dune and infiltrate the Outback.

8 Times

You might think a country 8 times the size of South Africa [and the world’s 6th largest country] would have 8 times more to offer, but unless you’re a sand salesman, you’d be wrong. Australia’s size means it’s moer far to get around. Nullaboor in Western Australia is as flat as a pancake. The track that crosses the Nullaboor is the world’s longest straight section of railway line in the world. Ja, it’s pretty boring.

Perth, 3300km from Sydney, is one of the world’s most isolated cities. Imagine having to travel from Cape Town to Pretoria just to get halfway to Johannesburg.

But the number one issue facing this mammoth country, believe it or not, is climate change.

Heat

Crime can seem like the worst problem in the world, but it’s fiddlesticks compared to Australia’s climate conundrum. It’s ironic that being the world’s number one coal exporter, Australia has the highest per capita level of emissions in the developed world, and they’re reaping a whirlwind of climate problems In February they have to endure constant, unbearable heat across the length and breadth of the country.

When I visited Melbourne’s average temperatures were the highest since records began. Many other centres set new all-time records too. It was hot, and rainfall was either absent or miserly figures like 0.2mm for the entire month. In Perth we measured the heat ourselves; at 7pm it was still 37 degrees Celsius. This heat turns Australia’s forests into a tinderbox, and when they burn the damage is catastrophic.

On a trip to the famous Pinnacles Desert two hours north of Perth the mercury shot up to 44C in Cervantes. Imagine standing with your ankles in the sea, and the rest of your body feeling like it is stuck in a gym sauna; the air so hot it pinches the soft linings of your nose. The Pinnacles is basically a graveyard of rocks in a sandpit the size of 5 rugby fields.

Humidity

I found the humidity a problem everywhere in coastal Australia, from Perth, to Sydney, with Darwin being the worst. Without an air conditioner in Australia you’re toast! At night you lie naked except for a scrap of underwear in your tent; you’re a pathetic, heaving foetus, trying to survive overnight in the sauna conditions. You’re covered in a permanent film of sweat, bugspray and sunblock. You wonder, maybe it’s your own body heat and breath causing the infernal heat in your tent – but when you open the tent flap at 4am it’s just as warm outside. And how do Australians suggest we cope with the infernal heat of the day? “Take hot showers,” they say.

Further up the coast of Western Australia is the attractive town of Broome, one of the fastest growing centres in Oz. It has camel rides on the beach, a section that boasts the largest collection of dinosaur footprints in the world [except it’s underwater] and special gutterless roofs because when it rains it pours so much the water literally rips the gutters off the eaves.

Jellyfish

Broome seems like a lekker place. Cable Beach has that classic sickle shape. But you realize something is wrong when it’s the height of summer, it’s mid to high thirties and uncomfortably humid, and despite the national holidays, not a soul is swimming in the sea.

It turns out that this is one of a bunch of nasty consequences of climate change haunting virtually the entire coastline: floating clouds of poisonous jellyfish and stingers. I scoffed at the warnings at first, until I was stung by something so small I couldn’t see it. It left a yellow bruise on my chest for weeks.

This was one of the most frustrating aspects of visiting Australia. The height of summer, and miles and miles of gorgeous coastline but it’s too dangerous to swim in the sea. When I visited the Great Barrier Reef we all had to pay for stinger suits, which effectively cover 90% of your body. But you can still get stung on exposed parts like hands, feet and cheeks. What’s the fun in swimming in summer dressed like a glove?

Wallabies VS Springboks

When the nickname for Australia’s national animal is also the longer version of a term we use to say someone ain’t too bright, you’ve got to hand the trophy to the Boks. In contrast to a Wally, a Bok is up for anything. Calling someone a Bok is a compliment. Kangaroos, in Africa, against our predators, wouldn’t last more than a few blinks after sunset. And that should put paid to the question surrounding whether the Wallabies are better than the SpringboksBut here’s the clincher. The fact that you can buy boerewors and biltong in Australia, and it's called boerewors and biltong, says a lot about what a lot we got. In every area we give Oz a real run for its money.

Monday, September 20, 2010

Getaway magazine [September 2010]

Wild, wild Shingwedzi

Nowhere is better for those close encounters than Kruger’s northern camp of Shingwedzi. Here the highest proportion of Kruger’s big 5 come out of hiding, with the biggest of the big 5 especially famous here. Now you know why people keep coming back to this camp – by Nick van der Leek

“We won’t stop for lion or leopard, as I’m sure everyone has seen enough of those.” Our Ranger, Matthew, about to take us on a game drive, reminds us how nature has been coming to us here, rather than the other way round. Just north and south of the Shingwedzi camp are some of Kruger’s largest concentrations of big 5 sightings. Vlakteplaas, on the northern side, gets the most, so concentrate your game viewing just north of the camp.

Hide and seek is the name of the game being played out in Nature day in and day out, and it can get a bit slow out there sometimes, looking for animals whose survival depends absolutely on a critter’s ability to remain unseen. The best wild places then are those where abundant animals come to you so you don’t have to go searching for them. But mention Shingwedzi and invariably you’ll hear someone say, “I love that place. We go there often.” And people come back to Shingwedzi for exactly the same reasons the animals do – they know what to expect; and they know they have a good chance of finding what they want.

Shingwedzi, incidentally, is derived from a Tsonga word that refers to the KRRR shriek of metal objects rubbing together. Perhaps it is a nod to the particular density of the regional foliage and animals that evokes this unusual noise, associated perhaps with material ‘closeness’.

Green and Warm

One of the reasons for Shingwedzi’s charm is it’s not the hive of human activity that other camps falling plum on the beaten track are, like Satara and those further south. But it’s more than that. Tanya and I are visiting in July, midwinter, but on this side of the Tropic of Capricorn it’s t-shirt warm, and the increasingly remote surrounds have gone from an autumn bronze, a lovely fiery orange in the rain-washed sunlight, to a brilliant, shining green, teeming with buffalo and elephant. That’s the other thing. Just this northern region of Kruger [as opposed to the far north and Punda] is home to more than half of Kruger’s elephant herds. Elephants are visible virtually every day in the riverine area close to camp and they’re often seen crossing the road. There's also a resident troop of baboons visible rampaging on the river’s sand flats just a kilometre from the camp entrance. These are a favourite food of another resident hunter, the leopard. The tall, dense, leafy surrounds are perfect for these predators.

The landscape is gently undulating bushveld with the occasional outcrop. These infrequent natural turrets sporting huge grey boulders are often home to baboons and some or other historical significance, such as those found at Red Rocks [where there is also a resident lion pride]. Kruger probably hasn’t changed since humans first arrived here. Well, other than a strip of tar and the style of the flashing vehicles sliding along these slim corridors.

We approach from the Phalaborwa Gate due to its proximity to the main highways, and the distance from greater Gauteng. For us the idea is to get into Kruger as soon as we can, but not necessarily to our camp. It’s 131km to Shingwedzi following the H-14 and H 1-6. Another option is Punda Maria Gate further north, but I’d suggest this as a better option for exiting the park than entering. Of course if you’re pressed for time [remember the speed limit inside the park is 50km/h] from Punda it’s half the distance compared to the Phalaborwa route at less than 70km to Shingwedzi. The Phalaborwa option presents a long leisurely road, an option that rewarded us with a mamba, puffadder, hyena and plenty of birds and elephants. The large number of buffaloes we saw almost certainly explains why so many lions are here, and Shingwedzi’s reputation for its record of big 5 sightings.

With the sun having just set, 6km left to Shingwedzi, and just 5 minutes to Gateline [Kruger jargon] we find the road in the distance blocked off by a wall of grey.

About 2km further we are delayed by a pair of ultra sensitive Great Eagle owls [also common to this area] silhouetted against the grey ashes of a cigarette sky. While they’re telescoping towards rustles in the grass, and we have long lenses focused on them, 3 vehicles pass us in quick succession. We set off, watching the time tick over to 5:31pm. This is the common dilemma visitor’s face. Arriving before gates close at faraway camps.

Lion Around

Just around the corner, with around 1km to go we find all three vehicles stopped dead, abreast of each other, and in their headlights, two beautiful lions, a large male and female, standing in the road. We’re on the main H1-6 road. The local ranger, Matthew, later informs me that this is a often seen breeding pair, and that there are three resident prides floating around Shingwedzi with the Babbelane pride being the biggest with 25. In fact southern Kruger has more lions

The female is very relaxed, enjoying the male’s riveted attention, she lounges on the warm tar while the male paces around her, paws her tail, sits, and makes another pass. Finally, one of the vehicles inches forward on the gravel of the right hand verge, and I slide into his slot. The male bristles at this encroachment; the vehicle inches further, and then the male advances with The Look, and the Toyota’s white reverse lights come on, and we’re back where we started. I hover for a moment and try a few moments later down the left verge. As we pass the Toyota the driver says to us, “Not a hell.” I go as far to the left as I can, hover, watch, and then see if they’ll let me pass. The lion lovers are so laid back, they won’t mind me. At about 3 metres the male is up and I hit reverse; next minute the lion is about to run so I stop [they say don’t run away from a lion, does the same apply to driving?], and he abruptly turns and goes back to his fiancé.

“He was right, ‘not a hell’.”

It’s interesting, sitting high off the ground, protected by a powerful capsule of metal and glass, and you have a male lion holding 4 vehicles with fines to pay, at bay. That’s power.

10 minutes later we’re through the gate, none the worse for wear. The lion encounter is a thrilling highlight to close off the day’s game viewing.

Mopane Country

Shingwedzi is nestled right beside the Shingwedzi River in mopane [aka elephant] country, close – but not too close – to the river’s flood level. This really does give visitors that ‘back to nature’ vibe. Unlike Olifants, which is perched high above that magnificent river, and has awesome scenery but is somehow a little detached from the surroundings, Shingwedzi’s camping sites, huts and bungalows conspire to create a community. So it’s kind’ve cozy. The limited use of paving, the tall palms elbowing the tall thatch cottages and the abundance of squirrel filled trees make Shingwedzi the sort of space that you want to braai in and sit around outside. There’s not much of a view, but isn’t that what game drives are for?

The next morning I walk between the camp’s fever trees and palms to note the recent sightings posted at reception. Everything, from leopard, to wild dog, and most of it on a dirt road that starts on the east side of the camp [right behind our bungalow where a Bateleur likes to brood]. So we follow the gravel road [23km along the S50] that skirts the Shingwedzi River. This is one of the best known drives in the whole Park. It has dozens of mini loops to get you closer to the river, and the elephants love this area for its massive trees towering over the verge of the river. It is here that we spot our first crocs, and a bunch of terrapins. Further down we see the bloated carcass of a hippo floating in the middle of the river, with a croc fastening a napkin to his throat before thrashing down some lunch. We also find bigger tuskers in this area, and we’re not surprised to learn that one of Kruger’s largest elephant males, Machichule, haunts this Shingwedzi River area. This Kanniedood Drive takes you south, down as far as the historic Dipeni dipping tank, linking up with the Mashagadzi Waterhole Loop on the S134.

The area around Shingwedzi is lovely and teems with life. It’s 200 metres lower than Punda Maria, so it’s warmer and greener here than just an hour or so further south, but be warned, William, the manager tells me July is usually full every year. During our visit there is a constant [and let’s admit, irritating] stream of vehicles. Although the rest camps offer drives, sometimes, often, you’ll see more from your own vehicle, and you can take it all in at your own pace.

Red Rocks

Another great day time trip is the Red Rocks Loop, across rivers, forest and woodlands along the S52. This route takes you to a number of viewpoints, and the Red Rocks site is just one to recommend. Eons ago the Shingwedzi River eroded a sandstone slab and cyanobacteria took over further decay. Look out for Dwarf Mongoose, vervet monkeys and elephants.

On our night drive the highlight was two Marshall Eagles sleeping in an Apple Leaf and a Bushbaby that most of us didn’t see [what does that tell you?]. We see a lot more here during the morning and late afternoon than after dark. Part of the reason for this is the vegetation is particularly closed and bushy around Shingwedzi. The local ranger, Matthew, says there is a resident pride of 14 lions so you’re virtually assured of seeing these on your visit. Also make sure to visit the Shingwezi Bridge just around the corner from the camp, where you are allowed to alight from your vehicle and take some photos. It was a very popular spot when we were there, and it’s a lovely place for sundowners and a quick social. Another useful spot close to the bridge is labeled ‘Confluence’ and is also worth checking out.

While braaiing under a sky shot through with stars on our last night, and using some locally purchased meat [and it must be mentioned, delicious] in front of our cottage, Tanya and I discuss the setting of the bush and animals at Shingwedzi, taking in some of the highlights of our day. Shingwedzi is so close to nature that in 2000 the restaurant overlooking the river was actually flooded.

“Did you notice how everything seemed to turn green as we crossed the Tropic of Capricorn?” I say.

“It started when we saw that rainbow, and when the sun started to really come out,” Tanya observes. If you’re looking for a pot of gold under a Kruger Park rainbow, you won’t find it. What you will find is a treasure of another sort – wild animals. Lots of them. And you can do far worse than the critters that come to you at Shingwedzi.

Nowhere is better for those close encounters than Kruger’s northern camp of Shingwedzi. Here the highest proportion of Kruger’s big 5 come out of hiding, with the biggest of the big 5 especially famous here. Now you know why people keep coming back to this camp – by Nick van der Leek

“We won’t stop for lion or leopard, as I’m sure everyone has seen enough of those.” Our Ranger, Matthew, about to take us on a game drive, reminds us how nature has been coming to us here, rather than the other way round. Just north and south of the Shingwedzi camp are some of Kruger’s largest concentrations of big 5 sightings. Vlakteplaas, on the northern side, gets the most, so concentrate your game viewing just north of the camp.

Hide and seek is the name of the game being played out in Nature day in and day out, and it can get a bit slow out there sometimes, looking for animals whose survival depends absolutely on a critter’s ability to remain unseen. The best wild places then are those where abundant animals come to you so you don’t have to go searching for them. But mention Shingwedzi and invariably you’ll hear someone say, “I love that place. We go there often.” And people come back to Shingwedzi for exactly the same reasons the animals do – they know what to expect; and they know they have a good chance of finding what they want.

Shingwedzi, incidentally, is derived from a Tsonga word that refers to the KRRR shriek of metal objects rubbing together. Perhaps it is a nod to the particular density of the regional foliage and animals that evokes this unusual noise, associated perhaps with material ‘closeness’.

Green and Warm

One of the reasons for Shingwedzi’s charm is it’s not the hive of human activity that other camps falling plum on the beaten track are, like Satara and those further south. But it’s more than that. Tanya and I are visiting in July, midwinter, but on this side of the Tropic of Capricorn it’s t-shirt warm, and the increasingly remote surrounds have gone from an autumn bronze, a lovely fiery orange in the rain-washed sunlight, to a brilliant, shining green, teeming with buffalo and elephant. That’s the other thing. Just this northern region of Kruger [as opposed to the far north and Punda] is home to more than half of Kruger’s elephant herds. Elephants are visible virtually every day in the riverine area close to camp and they’re often seen crossing the road. There's also a resident troop of baboons visible rampaging on the river’s sand flats just a kilometre from the camp entrance. These are a favourite food of another resident hunter, the leopard. The tall, dense, leafy surrounds are perfect for these predators.

The landscape is gently undulating bushveld with the occasional outcrop. These infrequent natural turrets sporting huge grey boulders are often home to baboons and some or other historical significance, such as those found at Red Rocks [where there is also a resident lion pride]. Kruger probably hasn’t changed since humans first arrived here. Well, other than a strip of tar and the style of the flashing vehicles sliding along these slim corridors.

We approach from the Phalaborwa Gate due to its proximity to the main highways, and the distance from greater Gauteng. For us the idea is to get into Kruger as soon as we can, but not necessarily to our camp. It’s 131km to Shingwedzi following the H-14 and H 1-6. Another option is Punda Maria Gate further north, but I’d suggest this as a better option for exiting the park than entering. Of course if you’re pressed for time [remember the speed limit inside the park is 50km/h] from Punda it’s half the distance compared to the Phalaborwa route at less than 70km to Shingwedzi. The Phalaborwa option presents a long leisurely road, an option that rewarded us with a mamba, puffadder, hyena and plenty of birds and elephants. The large number of buffaloes we saw almost certainly explains why so many lions are here, and Shingwedzi’s reputation for its record of big 5 sightings.

With the sun having just set, 6km left to Shingwedzi, and just 5 minutes to Gateline [Kruger jargon] we find the road in the distance blocked off by a wall of grey.

About 2km further we are delayed by a pair of ultra sensitive Great Eagle owls [also common to this area] silhouetted against the grey ashes of a cigarette sky. While they’re telescoping towards rustles in the grass, and we have long lenses focused on them, 3 vehicles pass us in quick succession. We set off, watching the time tick over to 5:31pm. This is the common dilemma visitor’s face. Arriving before gates close at faraway camps.

Lion Around

Just around the corner, with around 1km to go we find all three vehicles stopped dead, abreast of each other, and in their headlights, two beautiful lions, a large male and female, standing in the road. We’re on the main H1-6 road. The local ranger, Matthew, later informs me that this is a often seen breeding pair, and that there are three resident prides floating around Shingwedzi with the Babbelane pride being the biggest with 25. In fact southern Kruger has more lions

The female is very relaxed, enjoying the male’s riveted attention, she lounges on the warm tar while the male paces around her, paws her tail, sits, and makes another pass. Finally, one of the vehicles inches forward on the gravel of the right hand verge, and I slide into his slot. The male bristles at this encroachment; the vehicle inches further, and then the male advances with The Look, and the Toyota’s white reverse lights come on, and we’re back where we started. I hover for a moment and try a few moments later down the left verge. As we pass the Toyota the driver says to us, “Not a hell.” I go as far to the left as I can, hover, watch, and then see if they’ll let me pass. The lion lovers are so laid back, they won’t mind me. At about 3 metres the male is up and I hit reverse; next minute the lion is about to run so I stop [they say don’t run away from a lion, does the same apply to driving?], and he abruptly turns and goes back to his fiancé.

“He was right, ‘not a hell’.”

It’s interesting, sitting high off the ground, protected by a powerful capsule of metal and glass, and you have a male lion holding 4 vehicles with fines to pay, at bay. That’s power.

10 minutes later we’re through the gate, none the worse for wear. The lion encounter is a thrilling highlight to close off the day’s game viewing.

Mopane Country

Shingwedzi is nestled right beside the Shingwedzi River in mopane [aka elephant] country, close – but not too close – to the river’s flood level. This really does give visitors that ‘back to nature’ vibe. Unlike Olifants, which is perched high above that magnificent river, and has awesome scenery but is somehow a little detached from the surroundings, Shingwedzi’s camping sites, huts and bungalows conspire to create a community. So it’s kind’ve cozy. The limited use of paving, the tall palms elbowing the tall thatch cottages and the abundance of squirrel filled trees make Shingwedzi the sort of space that you want to braai in and sit around outside. There’s not much of a view, but isn’t that what game drives are for?

The next morning I walk between the camp’s fever trees and palms to note the recent sightings posted at reception. Everything, from leopard, to wild dog, and most of it on a dirt road that starts on the east side of the camp [right behind our bungalow where a Bateleur likes to brood]. So we follow the gravel road [23km along the S50] that skirts the Shingwedzi River. This is one of the best known drives in the whole Park. It has dozens of mini loops to get you closer to the river, and the elephants love this area for its massive trees towering over the verge of the river. It is here that we spot our first crocs, and a bunch of terrapins. Further down we see the bloated carcass of a hippo floating in the middle of the river, with a croc fastening a napkin to his throat before thrashing down some lunch. We also find bigger tuskers in this area, and we’re not surprised to learn that one of Kruger’s largest elephant males, Machichule, haunts this Shingwedzi River area. This Kanniedood Drive takes you south, down as far as the historic Dipeni dipping tank, linking up with the Mashagadzi Waterhole Loop on the S134.

The area around Shingwedzi is lovely and teems with life. It’s 200 metres lower than Punda Maria, so it’s warmer and greener here than just an hour or so further south, but be warned, William, the manager tells me July is usually full every year. During our visit there is a constant [and let’s admit, irritating] stream of vehicles. Although the rest camps offer drives, sometimes, often, you’ll see more from your own vehicle, and you can take it all in at your own pace.

Red Rocks

Another great day time trip is the Red Rocks Loop, across rivers, forest and woodlands along the S52. This route takes you to a number of viewpoints, and the Red Rocks site is just one to recommend. Eons ago the Shingwedzi River eroded a sandstone slab and cyanobacteria took over further decay. Look out for Dwarf Mongoose, vervet monkeys and elephants.

On our night drive the highlight was two Marshall Eagles sleeping in an Apple Leaf and a Bushbaby that most of us didn’t see [what does that tell you?]. We see a lot more here during the morning and late afternoon than after dark. Part of the reason for this is the vegetation is particularly closed and bushy around Shingwedzi. The local ranger, Matthew, says there is a resident pride of 14 lions so you’re virtually assured of seeing these on your visit. Also make sure to visit the Shingwezi Bridge just around the corner from the camp, where you are allowed to alight from your vehicle and take some photos. It was a very popular spot when we were there, and it’s a lovely place for sundowners and a quick social. Another useful spot close to the bridge is labeled ‘Confluence’ and is also worth checking out.

While braaiing under a sky shot through with stars on our last night, and using some locally purchased meat [and it must be mentioned, delicious] in front of our cottage, Tanya and I discuss the setting of the bush and animals at Shingwedzi, taking in some of the highlights of our day. Shingwedzi is so close to nature that in 2000 the restaurant overlooking the river was actually flooded.

“Did you notice how everything seemed to turn green as we crossed the Tropic of Capricorn?” I say.

“It started when we saw that rainbow, and when the sun started to really come out,” Tanya observes. If you’re looking for a pot of gold under a Kruger Park rainbow, you won’t find it. What you will find is a treasure of another sort – wild animals. Lots of them. And you can do far worse than the critters that come to you at Shingwedzi.

Getaway Magazine [September 2010]

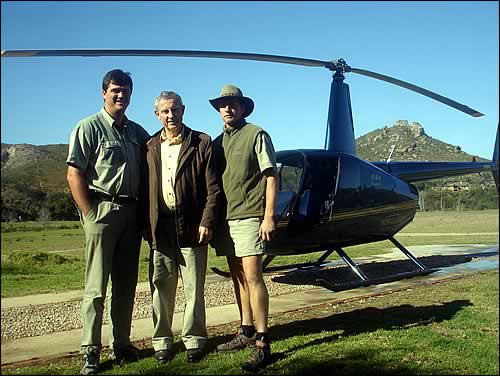

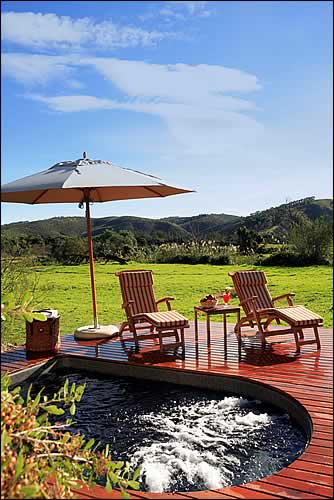

Shibula Lodge in leopard country – review by Nick van der Leek

“If you were a leopard, this is where you’d want to live.” During an afternoon game drive, Brett brought us home through a beautiful kloof hugging riverine brush forest. With the growing gloom of dusk throwing the headlights of the vehicle and the torchlight between twisting branches, it is easy to imagine one of the Big 5 watching us from some perfectly camouflaged position. It’s true, we watched it happen with a Cheetah: once a spotted coat stops moving, it immediately dissolves into the Waterberg’s pristine mountain bushveld.

Earlier this year, Brett, the ranger at Shibula Lodge in the Welgevonden Reserve, spotted a female leopard with her two cubs. They were in the bush just around the corner from the lodge. It turns out that statistics bear out these suspicions of ideal leopard terrain. A recent study conducted jointly by Lourens Swanepoel from the University of Pretoria and the Centre for Wildlife Management, using rotten eggs and fermented fish, they lured leopards into camera traps. Preliminary estimates are for about 30 leopards (22 adult & 8 sub adult and juveniles) on Welgevonden at a density of 6.1 leopards/100km², giving this area some of the highest density for leopard cubs in South Africa.

Shibula Lodge is an immersive experience, the lodge feels part of the surrounding landscape, and has a slight feng shui feel to it. This may be thanks to the individual plunge pools, or perhaps the delicious Kudu steaks. The view from the dining room balcony presents near symmetrical views as hillsides appear to rise and fall in mirror images on both sides.

Shibula has had a herd of elephants marching through the camp earlier in the year, and while we were there baboons shouted from the nearby rocks of a beautiful kloof. Lions are occasionally sighted too, around this Lodge, named after another Big 5 local, the Rhinoceros.

It’s a wonderful relaxing stay in the heart of the Waterberg, ideally situated [3 hours drive]for Gauteng’s city slickers.

Lodge Score: 4/5

Contact Details: +27 [0]882 82 06

+27 [0] 82 788 5100

Current specials: R1550 per person per night sharing – valid to 31 July 2010

Thursday, September 9, 2010

Luxury in the bush at Lukimbi

I first mistake the flashes up ahead for lightning. But it's three lions holding up traffic on the road to Lukimbi and the occupants of nine vehicles are photographing like there's no tomorrow in the growing dusk.

When we arrive at Lukimbi, in the greater Southern Kruger National Park, it's after dark and raining. My partner is grumpy and I'm just plain tired. We've been on the road for a few days now after covering over 4 000km - I am really hoping Lukimbi is every bit of its five-star rating. We pull in flustered and hungry and generally out of sorts. The valet parking service quickly gets the car and everything else out of sight and out of mind.

We're ushered through khaki interiors, warm without being dark, rich and romantic without being stiff or stifling. Our luxury suite feels like stepping into an intimate corner of a local village; it has some lovely thatched nooks and crannies, lots of asymmetrical designs which someone went to a lot of trouble to conjure up and then build. Very quickly we're very sorry that we didn't arrive hours earlier, because it is so easy to just love being here.

And Lukimbi, it turns out, wins the Kerfuffle Award.

Read the rest.

When we arrive at Lukimbi, in the greater Southern Kruger National Park, it's after dark and raining. My partner is grumpy and I'm just plain tired. We've been on the road for a few days now after covering over 4 000km - I am really hoping Lukimbi is every bit of its five-star rating. We pull in flustered and hungry and generally out of sorts. The valet parking service quickly gets the car and everything else out of sight and out of mind.

We're ushered through khaki interiors, warm without being dark, rich and romantic without being stiff or stifling. Our luxury suite feels like stepping into an intimate corner of a local village; it has some lovely thatched nooks and crannies, lots of asymmetrical designs which someone went to a lot of trouble to conjure up and then build. Very quickly we're very sorry that we didn't arrive hours earlier, because it is so easy to just love being here.

And Lukimbi, it turns out, wins the Kerfuffle Award.

Read the rest.

Friday, July 23, 2010

Raynard's Return [published in June TRIATHLETESA Magazine]

How do you win an Ironman? Is there a magic formula [as there is for the Tour de France?] I asked South Africa’s toughest athlete, 2010 Ironman winner Raynard Tissink to shed some light on what it means to be an Ironman Champion again, and again – by Nick van der Leek.

“No,” Raynard says, “there unfortunately is NO magic formula. If there was, I probably would not have finished 2nd for 3 consecutive years. It all comes down to proper preparation and more importantly putting everything together on race day. I went into the last 4 IMSA events, confident that I was in excellent shape and that I would be in a position to win. Punctures, pure nutrition, illness and other outside factors played a part in how those races turned out.”

So luck is a factor. You can improve your chances with preparation, and even push yourself into being a virtual certainty, but Lady Luck also comes into play, especially during a race as epic and filled with possibilities as the Ironman.

“So you can never be guaranteed going into a race that things will work in your favour. I think every IM athlete goes into the event hoping for a perfect day, hoping that his nutrition, his mechanics, his health, his energy will be good on that day. The only thing you can guarantee is putting in the work before hand.”

Tell us about the lowest point you were at before this win. You had a few injuries and so on. When was your motivation at rock bottom and what did you do?

“I think the lowest part was last year when I had to withdraw at 7km into the marathon of IMSA. I didn't know that it was asthma, and thought the chest pain was maybe related to heart problems. I thought that this was maybe the end of my career. But, after visiting specialists, discovered that it was asthma and that it was treatable.

Of course, everyone thought that it was an excuse and that my days were numbered. What more motivation do you need - other than to prove everyone wrong!”

How confident were you of your chances going into this one?

“Hey, every race I enter, I enter to win. So, of course I was confident of my abilities. I think my injury to my ankle which forced me out of the 70.3, and forced me to rest was a blessing in disguise. I had 2 complete rest months and only started training in January. Honestly, I wasn't sure whether I had enough training in me, because I know everyone else had been training since Sep/Oct last year already. BUT, the training I had put in had gone really well, so I was hoping for a good performance.”

And why was that?

“I had put in some really big bike weeks prior to the race in AbuDahbi and my biking in that race had gone really well. I had also focused more on my running, and with the help of Alec Riddle (who has coached many of SA's top marathon runners), I was confident of my running abilities as well.”

Please talk us through this race. Did everything go according to plan?

“No, nothing went according to plan. My plan had been to swim with the leaders, sit back on the bike and run really well. As it turned out, I had a bad swim, and came out 3 minutes behind the leaders. This changed my plan completely. So, I decided to still hang back on the bike, but at 100km we were just on 7mins behind and I couldn't hold back any longer. I felt the guys around me were getting too weak and decided to put in a burst of speed to break things up.

At 160km the gap to the front was about 4min, but after 60km of hard riding it was time to back off again to recover for the run. Even so, my legs were still a little tender coming home but the body and mind were ready to hammer. I also managed to pick up Anton Storm in the last 5km which meant I was up into 4th position off the bike. After a leisurely transition, I set off on my marathon. [Mathias] Hecht was leading @5,5min. Anton Storm @3,5min and Daniel Fontana @2min. James [Cunama] was 4,5min back, so by no means out of the picture. I tried to start slow for the first 2km, trying to let the legs loosen up a little, but 3:49 and 3:56k's didn't help that cause. So, I decided to just go for it. I felt fantastic, so just kept going, and luckily for me - it paid off.”

When Lance broke his collarbone last year during the Tour of Italy people thought that was it, and yet within a remarkably short time he came back. There was a study done with university students where they showed if they were forced to lie down for 2 weeks they could lose up to 10 years of physical conditioning. So after that injury, to your ankle I believe, what were you doing? Do you head to the gym in a cast and strengthen arms, how does it work?

“As I mentioned above, I had a complete rest for 2 months. It was great to actually have 1 Christmas with the family where they didn't have to fit everything in around my training.”

Are you on Twitter?

“Yes, raytissink”

On Facebook you describe what you do as: 'Wake up early, sweat blood all day, finish work late, go to sleep, repeat 7 days per week.' When do you rest? What happens the day after an Ironman win? How long does it take before you're training again?

“I've taken 2 weeks slowly now. Rested for 2 complete days, then started swimming again. Only ran and cycled again a bit in the 2nd week. This is now the 3rd week after the race, and training is back into full swing now for the races ahead.”

Okay a few very specific questions: what was your resting heart rate, average heart rate on the 25th/and maximum? What's your current body fat %? How did these compare to other Ironman races and is it something you try to stick to?

“I have no idea what my HR was as I don't race with a HR monitor. My current body fat is 6%.”

What do you have a background in? And do you think you can go faster than a 2:52 [Raynard ran a 2:52 in the March 25 Ironman?

“I used to run cross country at school and then got into canoe triathlon originally. Yes, Natalie helped with my swimming. It was by far my weakest discipline when I started. I have run a 2.49 marathon in an IM before - at IM Austria in 2005. I definitely think I can still go faster than that.”

Do you still use Moducare for your immunity? What about Vitamin B complex?

“I believe 100% in Moducare. I also take Vit B, C, Iron, Zinc and magnesium.”

You're going to Hawaii - what's your 'handicap' there, and what are you aiming for?

“I'm hoping to go to Hawaii. Yes, I've taken the slot, but unless we can come up with R150 000, we won't be going. Any South African travelling to Hawaii has a huge handicap competing in Kona. The time change is 12 hrs, the travelling time is 36hrs, the heat and humidity is extreme. So, a South African training alone over here, and then hoping to go over a couple of weeks in advance is wasting their time. You need to base your self in the same conditions and train with and race against the World's best if you want to realistically compete with them.”

Will you be doing any specific races before Hawaii, even smaller cycle or run events?

“I am racing a 70.3 event in Germany on June 5th. Then I am doing the Challenge France race on June 13th. I will also be racing the ITU World Long Distance Championships on Aug 2nd. If I can raise the money for Hawaii, I will race 2 more 70.3 events in the States before Kona.”

I have trained with Ryk Neethling who is about 8 years younger, and I've raced with you a long time ago and seen you race - it seems strange that you haven't shared, or seemed to want to pursue the sort of public exposure Ryk has. Is that intentional? Ryk did win Olympic medals, though none of them individual - did you never think of going on that sports-celebrity path? Endorsements based on looks? Because it's tough making money in sport in South Africa, especially triathlon, and you seem to maintain quite a low profile. Is this because you're training so much that you're not really finding time [or wanting] to market yourself?

“Hey, I think Ryk had the right contacts at the right time and I'm sure he's made a lot of money from it. It does take a lot of your time away from actual training and racing though. Luckily, I have fantastic sponsors that support me, like TRI SPORTS, GU, PUMA,CERVELO, MODUCARE and ACTION CYCLES. They have enabled me to get to where I am today. If it wasn't for their support, I probably would have been forced to retire a long time ago.

Is triathlon - as a career - getting any easier?

“No, as mentioned above, if it wasn’t for outside sponsors, it would be impossible to make a living as a professional Ironman triathlete. Federations are making it harder to earn prize money, and prize money has even dropped in some events.”

You're 36 now, Dave Scott was 40 when he came 2nd in Hawaii's World Champs, and 5th as a 42 year old. Is Raynard thinking of retiring?

"I’m only 36, so NO - No thoughts about retiring yet. I think I’m in the best shape of my life right now, and I know I can still improve even more.”

“No,” Raynard says, “there unfortunately is NO magic formula. If there was, I probably would not have finished 2nd for 3 consecutive years. It all comes down to proper preparation and more importantly putting everything together on race day. I went into the last 4 IMSA events, confident that I was in excellent shape and that I would be in a position to win. Punctures, pure nutrition, illness and other outside factors played a part in how those races turned out.”

So luck is a factor. You can improve your chances with preparation, and even push yourself into being a virtual certainty, but Lady Luck also comes into play, especially during a race as epic and filled with possibilities as the Ironman.

“So you can never be guaranteed going into a race that things will work in your favour. I think every IM athlete goes into the event hoping for a perfect day, hoping that his nutrition, his mechanics, his health, his energy will be good on that day. The only thing you can guarantee is putting in the work before hand.”

Tell us about the lowest point you were at before this win. You had a few injuries and so on. When was your motivation at rock bottom and what did you do?

“I think the lowest part was last year when I had to withdraw at 7km into the marathon of IMSA. I didn't know that it was asthma, and thought the chest pain was maybe related to heart problems. I thought that this was maybe the end of my career. But, after visiting specialists, discovered that it was asthma and that it was treatable.

Of course, everyone thought that it was an excuse and that my days were numbered. What more motivation do you need - other than to prove everyone wrong!”

How confident were you of your chances going into this one?

“Hey, every race I enter, I enter to win. So, of course I was confident of my abilities. I think my injury to my ankle which forced me out of the 70.3, and forced me to rest was a blessing in disguise. I had 2 complete rest months and only started training in January. Honestly, I wasn't sure whether I had enough training in me, because I know everyone else had been training since Sep/Oct last year already. BUT, the training I had put in had gone really well, so I was hoping for a good performance.”

And why was that?

“I had put in some really big bike weeks prior to the race in AbuDahbi and my biking in that race had gone really well. I had also focused more on my running, and with the help of Alec Riddle (who has coached many of SA's top marathon runners), I was confident of my running abilities as well.”

Please talk us through this race. Did everything go according to plan?

“No, nothing went according to plan. My plan had been to swim with the leaders, sit back on the bike and run really well. As it turned out, I had a bad swim, and came out 3 minutes behind the leaders. This changed my plan completely. So, I decided to still hang back on the bike, but at 100km we were just on 7mins behind and I couldn't hold back any longer. I felt the guys around me were getting too weak and decided to put in a burst of speed to break things up.

At 160km the gap to the front was about 4min, but after 60km of hard riding it was time to back off again to recover for the run. Even so, my legs were still a little tender coming home but the body and mind were ready to hammer. I also managed to pick up Anton Storm in the last 5km which meant I was up into 4th position off the bike. After a leisurely transition, I set off on my marathon. [Mathias] Hecht was leading @5,5min. Anton Storm @3,5min and Daniel Fontana @2min. James [Cunama] was 4,5min back, so by no means out of the picture. I tried to start slow for the first 2km, trying to let the legs loosen up a little, but 3:49 and 3:56k's didn't help that cause. So, I decided to just go for it. I felt fantastic, so just kept going, and luckily for me - it paid off.”

When Lance broke his collarbone last year during the Tour of Italy people thought that was it, and yet within a remarkably short time he came back. There was a study done with university students where they showed if they were forced to lie down for 2 weeks they could lose up to 10 years of physical conditioning. So after that injury, to your ankle I believe, what were you doing? Do you head to the gym in a cast and strengthen arms, how does it work?

“As I mentioned above, I had a complete rest for 2 months. It was great to actually have 1 Christmas with the family where they didn't have to fit everything in around my training.”

Are you on Twitter?

“Yes, raytissink”

On Facebook you describe what you do as: 'Wake up early, sweat blood all day, finish work late, go to sleep, repeat 7 days per week.' When do you rest? What happens the day after an Ironman win? How long does it take before you're training again?

“I've taken 2 weeks slowly now. Rested for 2 complete days, then started swimming again. Only ran and cycled again a bit in the 2nd week. This is now the 3rd week after the race, and training is back into full swing now for the races ahead.”

Okay a few very specific questions: what was your resting heart rate, average heart rate on the 25th/and maximum? What's your current body fat %? How did these compare to other Ironman races and is it something you try to stick to?

“I have no idea what my HR was as I don't race with a HR monitor. My current body fat is 6%.”

What do you have a background in? And do you think you can go faster than a 2:52 [Raynard ran a 2:52 in the March 25 Ironman?

“I used to run cross country at school and then got into canoe triathlon originally. Yes, Natalie helped with my swimming. It was by far my weakest discipline when I started. I have run a 2.49 marathon in an IM before - at IM Austria in 2005. I definitely think I can still go faster than that.”

Do you still use Moducare for your immunity? What about Vitamin B complex?

“I believe 100% in Moducare. I also take Vit B, C, Iron, Zinc and magnesium.”

You're going to Hawaii - what's your 'handicap' there, and what are you aiming for?

“I'm hoping to go to Hawaii. Yes, I've taken the slot, but unless we can come up with R150 000, we won't be going. Any South African travelling to Hawaii has a huge handicap competing in Kona. The time change is 12 hrs, the travelling time is 36hrs, the heat and humidity is extreme. So, a South African training alone over here, and then hoping to go over a couple of weeks in advance is wasting their time. You need to base your self in the same conditions and train with and race against the World's best if you want to realistically compete with them.”

Will you be doing any specific races before Hawaii, even smaller cycle or run events?

“I am racing a 70.3 event in Germany on June 5th. Then I am doing the Challenge France race on June 13th. I will also be racing the ITU World Long Distance Championships on Aug 2nd. If I can raise the money for Hawaii, I will race 2 more 70.3 events in the States before Kona.”

I have trained with Ryk Neethling who is about 8 years younger, and I've raced with you a long time ago and seen you race - it seems strange that you haven't shared, or seemed to want to pursue the sort of public exposure Ryk has. Is that intentional? Ryk did win Olympic medals, though none of them individual - did you never think of going on that sports-celebrity path? Endorsements based on looks? Because it's tough making money in sport in South Africa, especially triathlon, and you seem to maintain quite a low profile. Is this because you're training so much that you're not really finding time [or wanting] to market yourself?

“Hey, I think Ryk had the right contacts at the right time and I'm sure he's made a lot of money from it. It does take a lot of your time away from actual training and racing though. Luckily, I have fantastic sponsors that support me, like TRI SPORTS, GU, PUMA,CERVELO, MODUCARE and ACTION CYCLES. They have enabled me to get to where I am today. If it wasn't for their support, I probably would have been forced to retire a long time ago.

Is triathlon - as a career - getting any easier?

“No, as mentioned above, if it wasn’t for outside sponsors, it would be impossible to make a living as a professional Ironman triathlete. Federations are making it harder to earn prize money, and prize money has even dropped in some events.”

You're 36 now, Dave Scott was 40 when he came 2nd in Hawaii's World Champs, and 5th as a 42 year old. Is Raynard thinking of retiring?

"I’m only 36, so NO - No thoughts about retiring yet. I think I’m in the best shape of my life right now, and I know I can still improve even more.”

Tuesday, July 6, 2010

Feature in June 2010 GETAWAY Magazine

Going Boldly Into Botswana

The Kalahari wilderness has a flow of life like nowhere else on Earth. It is a place of abundant sun, sweat and sand. It teems with tough survivors. For an authentic wilderness experience you have to go boldly forwards, through the wet and the dry. Having a tough vehicle and a stubborn spirit for adventure can’t hurt your chances here – by Nick van der Leek

Once through the Martins Drift border, I drive the Land Rover as far inside Botswana as one can manage in an afternoon. With light fading at the end of a long first day, at about 900km from Bloemfontein, not far from a local village, I take us off the unfenced tar road to a rural village. We arrange with the locals to camp in the bush since it’s an emergency camp of sorts, and there’s nothing around here for miles. After handing over a small donation we settle in at our campsite about 500m from the road. With the melancholy ring of cow bells we drift off into a much needed sleep. No more sounds of the city. In the bush at last.

I’m with – Hennie Butler – a lecturer at Free State University’s department of Zoology and Entomology. This is our first camp on a 3500km, 10 day journey. It’s not only Hennie's extensive knowledge of animal behavior that makes for a fine companion [he’s currently working on his doctorate], but his quest for adventure.

We first experienced the wet…

We first experienced the wet…

It’s an early start the next morning. At 7am we begin the next 600km leg. We are heading west towards Maun via the southern route to Mopipi then further north, towards the eastern fringe of the Okavango Delta. We arrive at Letlhakane but are unable to refuel here. They have run out of diesel. We drive 15km further, to the modern, highly westernized diamond enclave of Orapa. To gain access to this closed society one needs a permit. It doesn’t cost anything, except time and documentation. Inside we find a highly functional operation, complete with Woolworths, Wimpy and What not. Well, we’ve never seen Orapa town so as often happens on a trip a negative turns out to be a positive.

We ride past Mopipi located on the south east edge of the Makgadikgadi Pans and northwards parallel to the Boteti River. The Boteti for the last 10 years has been mostly dry riverbed, except a few pools. We pop in to check out the river at the entrance to the Makgadikgadi Game Reserve near the main road. The river is in flood. Trees are under water and the park inaccessible from this side. We recall one of our first trips, perhaps 20 years ago when we crossed the Boteti as a swollen river. Our trailer actually floated as we crossed.

We’re back on the long tar road north to Maun, wondering what the water level is going to be like there. At 4pm on Day 2, we enter Maun, on the eastern fringe of the Delta. What used to be an almost derelict outpost, a frontier town leading into the Okavango, the tar road that has brought us here has also brought bustle to Maun.

“I remember when we used to get stuck in Maun.” Hennie remarks and he’s referring to sand, not traffic. Now Maun has parking fees. Maun has attracted, as in RSA many Zimbabwean refugees, and also, crime, though not enough for South Africans to sniff at.

Botswana is a hand gun free society, and its government is virtually corruption free and proud of the fact. Ian Khama, the President, changed the liquor laws so that stores open later, at 10am, and bars close earlier, at 10pm. He is a disciplined man and avid supporter of wild life. This bodes well for Botswana.

The river flanking the Okavango Safari Lodge where we’re spending our second night is also flowing strongly. It has already risen about 2 meters, since the fence alongside peeps occasionally through the flowing dark green. All this water isn’t endemic either. The summer rains in Angola, have gradually flowed south from those distant drainage basins through to the Kalahari Thirst land, the Delta and beyond to the Boteti system and also to Lake Ngami.

The Selinda Spilway, north of the Delta is flowing and the two river systems of the Okavango and Zambezi have now joined up at Linyanti. The Savuti Channel is running for the first time since 1983 but has not reached Savuti yet at the time of writing. The sandy river bed is very dry and sandy so the progress is very slow.

Lake Ngami, about 100 kilometers south west of our position in Maun [due south of the Okavango watermark] is full of water after being a dust bowl for 20 years or more.

60 years ago, the explorer David Livingstone described the lake as a "shimmering lake, some 130 km long and 15 wide".

“The locals laughed at you few years ago if you asked them for directions to this lake filled with water,” I say to Hennie. “As far as they’re concerned it was always just an endless dust bed. Until now.”

Contemporary maps show the lake has shrivelled to no more than 35km in length. But the history of the area is worth remembering.

Livingstone scribbled a few cultural notes at the time, describing the locals (Missionary Travels, chap. 26) as being in pursuit of a Tower of Babel experience, but this plan was scuppered [like all the other Babel Projects] when scaffolding fell onto large numbers of builders and ‘cracked their heads’. There’s further evidence of other African traditions particular to this Babel story thanks to research conducted by Scottish social anthropologist Sir James Frazer. In Ghana the Ashanti’s unfortunate quest involved the piling up of porridge pestles. Frazer also fingers folks along the Zambezi, in the Congo and Tanzania, where trees or poles are stacked in a failed bid to reach the moon.

With the half moon floating overhead, the fading African sunset reflecting in the water slowly flowing past the lodge, Hennie and I walk through the semi-submerged braai places to the pleasant casual atmosphere of the local lodge restaurant. Over Hennie’s chicken schnitzel and my spaghetti bolognaise, we debate the copious water flows around us.

What is Hennie’s opinion on this? “It might be part of a bigger cycle and changes in the flow of the various channels in the Delta,” he says.

One thing is certain; we’re in a Botswana that is exceptionally wet this spring.

Mopane Madness in Moremi

On Day 3 we leave Maun and the final strip of tar road at Shorobe, and begin to enter real wilderness. We’re skirting the wet fingertips, the easternmost fringes of the Okavango on our way to Moremi, and with each passing kilometre the vaal yellow tones that have been with us since the Free State are becoming increasingly luxuriant, with tall Mopane and Acacia trees dominating the landscape. We arrive at South Gate, the Maun side entrance to Moremi Wildlife Reserve.

Now our surroundings become tall, lush woodlands mixed together with lily-filled waterholes. Some of the forests are stunted, and it isn’t long before we see how this happens.

At around mid-morning we watch from the vehicle as a medium sized bull elephant pushes over a 10 metre Colophospermum, or Mopane tree. The Latin name means oily seed. A few seconds after a sharp KA-CRACK of hard wood snapping, two or three other elephants immediately advance steadily towards what must be a delicacy to them. While we watch the elephants graze, Hennie shares his thoughts as to why the elephants should favour the content of the branches and leaves of the fallen tree as opposed to the Mopane shoots that sprout everywhere from previously fallen tree stumps.

“These guys like it,” he says, nodding to the chomping elephants, but many other animals need time to get used to the sharp turpentine smell of Mopane resin.”

When we replay the video recording it’s clear that these elephants do have a strong appetite for the Mopane’s compound, butterfly-shaped leaves. It’s an entirely African product, this tree, as African as the African elephant.

Why are these trees not found in abundance further south? Because they’re neither cold nor frost resistant, and they prefer the ‘Cotton soils’ of the area which have a higher clay content than the adjacent sand areas. The name ‘Cotton soil is derived the soil where cotton grows so well in the southern states of the USA.

“Did you know,” Hennie says, “that the Mopane is part of a broad family of plants [Fabaceae] related to peas, acacias, even the red bush tea plant?’ Hennie’s expert knowledge always adds a lot of depth and insight to our trips; he’s a great guru to have at your campfire at the end of the day.

Mopane trees are not only eaten by elephants, but by an entire spectrum of creatures. Hard-nosed hornbills nest in the cavities of the Mopane’s durable, termite resistant trunks. Various creatures even smaller, are specialists when it comes to the Mopane. There’s the honey making mopane bee for example, Plebina denoita, and the sweet, waxy sap-sucker Arytaina mopani. These transform from succulent worms into leaf-hoppers. Mopane worms, a delicacy of the locals, are the caterpillar of the emperor moth, but many other species of moth and butterfly nourish themselves on this remarkable tree.

We drive further through the reserve; the abundance of wildlife is enthralling but not unusual. Although we’d booked ourselves into Camp 6 at Kwai Gate which is in front and overlooking a clearing where the animals congregate, when we arrive we find other people there. We decide to set ourselves up at Camp 4 instead. All the sites are relatively close to one another, set around newly built modern ablution facilities.

Towards sunset we watch impala and a small herd of buffalo congregating in the clearing in front of us. In the background we are aware of new arrivals, coming in apparently from Savuti. They appear to be Hollanders. While the buffaloes are congregating I notice a fellow moving off into the bush wielding an axe. It isn’t long before his efforts start echoing around us, and the buffaloes aren’t the only one’s getting irritated by this. Finally I get up and approach the guy, and point out that his chopping is chasing away the wildlife. We offer him some of our wood which he accepts gracefully. Problem solved.

When I return I find Hennie is setting camera traps for the night. After a braai under the moonlight and some discussion over gin and tonic and the odd whiskey, we sit with our backs to the Land Rover and the fire, listening to the haunting calls of hyenas. People often sit around a fire with their backs exposed. Fire is no protection from hyenas, worth noting since two people have recently been grabbed from behind by hyenas in Moremi. Hennie has awesome night vision, so I feel safe, but in the day, all day, he hides behind sunglasses. That night I sleep in a roof top tent and Hennie in the Land Rover.

After going through footage of Spotted Hyena from the camera traps the next morning, we spend our second day in Moremi venturing further east. As we’re driving, talk is around hyenas.

“They don’t have the presence of lions and herein lies the danger,” I say.

“They’re very ‘skelm’, “ adds Hennie. “They come into camp looking for food, whereas lions are more inquisitive, especially the sub-adults who like teenagers often come to see the bright lights only.”

“Lions may be safer than hyenas,” I say to Hennie, “but they’re still wild animals. I’d like to sit one night around the campfire while lions walk around, but I haven’t managed to do that yet. When you see them, they give you that look, and there’s no question. It’s into the car, pronto. ”

“Which is why you’re still sitting here,” Hennie grins.

“The other thing is when you’re drinking you’re less vigilant.”

“You’re braver than normal, and that’s dangerous.” Hennie agrees.

We’re seeing plenty of waterbuck, impala and kudu grazing in the underbrush. There are also plenty of elephants and lechwe everywhere. There is lots of water, so vehicle tracks are often blocked by flooded pans, but we manage to avoid getting stuck this time. Actually it’s no sin to get stuck. You should take calculated risks, and enjoy the adventure if something goes slightly wrong.

We spend our second night in camp 7 and Hennie once again sets up his camera traps. There are no buffaloes tonight, just a flock of hornbills turning the sand into a feathery carpet.

The next morning Hennie shows me images of more hyenas and black backed Jackal and a lion that passed the camp that night. We go along the Kwai River. This area of Moremi is so beautiful we decide to call it ‘Eden’. The elephants here are having a ball; swimming, climbing over each other, fully submerging with only their trunks above water, generally having an absolute – er – whale of a time.

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen elephants having so much fun.” I say to Hennie. He simply nods, without saying anything.

Hennie begins photographing the impressive scene in front of us. One other vehicle saunters by slowly and the driver gives a thumbs up to me through the window.

Stampede

For perhaps half an hour we absorb this beautiful African scene; 15 hippos lazing the daylight hours away, the elephants, playing and splashing, the sparkle of water flowing off their wrinkled, glistening black bodies.

And then, for no apparent reason, we watch this tranquil scene turn to mayhem. In a moment, the elephants collectively and inexplicably charge out of the water trumpeting. A hell of a din. All of them seem to have panicked at the same time. They turn the waters into seething white spray, and over the roar of heavy legs galloping through shallow water we hear shrieks and bellows. They continue, perhaps thirty of them, altogether, charging through the water to the opposite bank, along the river in front of us and then 200m upstream; storming at full speed back across the river again and then storming off cross country, still trumpeting into the thick bush until they are out of sight. Our tranquil scene, in a matter of seconds, has turned to dust and the violent churning of muddy water they’ve left behind. You can almost see the eyebrows of a few dumbstruck hippos lifting quizzically over their partially submerged heads: “And now?”

Despite the elephants having gone, we can still hear a commotion of branches cracking and distant shrieks of utter panic as those still wet bodies continue lumbering en masse through the woodlands.

Hennie and I spend the rest of the day conjecturing as to what set the elephants off on such a dramatic stampede.

“Maybe they caught our scent, as they were down wind of us…”

“And at the same time caught a glimpse of the reflection of the camera’s lens in the late afternoon sun…

“Which awakened memories of telescopic gun sights used by hunters…perhaps in neighbouring Zimbabwe?”

“To have triggered such a response they must have remembered something tragic to the herd……and they don’t forget! “

“Maybe a submerged hippo was disturbed and nipped the matriarch who panicked and set off the rest…” Maybe, maybe we will never know.

The hippos though aren’t complaining. About fifteen of these quizzical animals are still in the water, moving, snorting: ‘oim, oim, oim’

When the sun begins to set we’re still here, sitting in our camping chairs overlooking the same hippo-filled scene. It has been a helluva day and we’re reluctant to return a moment too soon to camp 7. We decide instead to soak up as much as we can here before driving back to camp.

The sky is turning orange, then pink, and all this reflecting in the hippo’s darkening day time refuge. Over several minutes we notice these big beasts beginning to leave the water in the cool evening to graze maybe as far as 3km into the bush.

Charge

We are enjoying the sunset in the water when I notice a hippo walking, can it be, slowly but with purpose, directly towards us!

The hippo simply comes closer, and something about the tilt of its head makes it clear that its intentions aren’t benign. A young bull we think. The hippo charges. And stops. A mock charge.

“Hier’s moeilikheid”, I say in Afrikaans (here’s trouble,) While I’m glancing at the door of the land Rover behind us, wondering whether two of us will be able to scramble through that space at the same time, the hippo charges again. Hennie grabs the lid of the trommel, stands up, lifting the lid directly over his head. The hippo immediately stops and hesitates for a moment. Hennie lowers the lid and suddenly the hippo lurches forward. Hennie raises the lid again, and finally after the third time, the hippo decides to walk around our temporary setup rather than going straight through. Hennie nervously explains that the lid above his head makes him look bigger and thus more intimidating to the Hippo. Clever man!

“I think they get nervous when it gets dark,” Hennie – the Gladiator – says, still holding onto the trommel lid.

Once we feel he’s safely out of our hair, we pack our chairs and make haste to arrive back at the nearby campsite before the gates close.